They woke me up for breakfast: a cereal bar, a banana, and a custard cup of orange juice with a foil top. Clunk, clunk is the sound of Ghana coming up under the wheels. Soon we are stopped and people are prying their plaid jute bags from overstuffed overhead compartments, and when the cabin door is opened the air rolls in like a hot fog. Down the stairs, across the tarmac, through the queue to the immigration officer whose accent is, for a second, too thick to make out. He is asking me how many books I’ve written, and whether I’m famous enough that he should get my autograph. On my entry card I’ve listed my occupation as “Writer”.

Outside I can taste the dust. It’s the Harmattan, O the evil Harmattan and its choking haze! Last year I lost my voice for two weeks when the cruel silt took up residence in my throat. It makes the morning sky look like a big brown smudge left by a junky pencil’s hardened eraser. And the taxi drivers, so anxious to help me home. Only GHC 15, you say?

It feels pretty automatic this time around. The lively taxicab tango (resulting in a fare of GHC 3) is a well-rehearsed show for no audience. When my pants start to stick to my shins after four minutes outside, I make a mental note: that’s probably twice as long as it’s ever taken before. After eight months of preparation the plastic sheeting has been removed from the edge of Cantonments Roundabout—also known as Deforestation Circle, for its center island full of venerable old trees that were chopped down in an effort to drive away the prostitutes known to hide from the police in their shadows at night—revealing an area of sparse grass with a sizeable podium in the middle. The statue on the podium is hidden under a cloak of garbage bags. My house has not moved, but the pitted track that runs in front of it has seen some repairs, as the deepest potholes have been filled with loose chunks of cement.

So some things are different; others are the same.

I walked into an empty house, put down my bags, and fell asleep. The first couple days always feel slow and arduous. I notice things that aren’t: the hours aren’t passing; the air isn’t crisp; the loved ones aren’t around; the acquisition of a good meal isn’t likely; the shower isn’t hot and the pressure isn’t good. Happily,

CAN 2008 is the biggest thing since Ghana@50. It’s the African Cup of Nations, the continent’s most soccer tournament, held every other year. From January 20 – February 10,

In

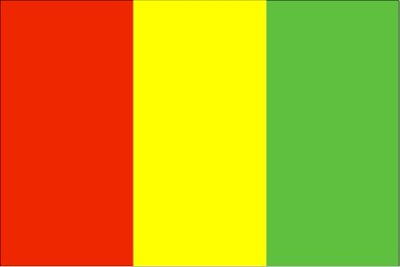

The people are also keeping up with the masonry. Every car—yes, every car—has at least one Ghanaian flag visible in or on it. Sales of whistles and plastic horns are through the roof. The plastic horns are in green, red, or yellow and they make a triumphant elephant sound. Those who can beg, borrow, or steal for them have bought CAN 2008 shirts. There are no less than 100 unique styles.

It’s not just for

So it is a real to-do, a combination of competition and pageantry that amounts to something like a medieval joust on safari. As such, it is not to be missed.

A well-connected manager at the office who has been sidelining with the company printing tickets for the entire tournament managed to wrangle one for me: blue section 13, seat S0050 of the popular stands (cheap seats) for the opening match. I gave that one to George to ensure his attendance; then when Sunday came we went to the stadium at midday to try our luck with the scalpers. How do we look?

It was, as expected, a madhouse. All the red, yellow, and green paint in the city seemed to have been bought up and used to color the people walking around. They had been dipped like dark fried meat in fondue. It wasn’t too hard to find a ticket. It cost GHC 30 for a GHC 4 ticket, but that was what the market would bear. George feigned outrage (or wasn’t it feigned?) at the scalper, who happily exchanged blue section 12, seat U0002 for my three green bills. He added them an ample stack which he folded neatly in half and put in his pocket.

With tickets in hand we took some time to amble around the outside of the stadium and see what was going on: mostly rowdy fans and the noise of plastic horns, whistles, kazoos, and foghorns is what it was. One guy, though, was handing out little glossy prayer-a-day booklets, and another was promoting Trashybags, a neat organization that makes handbags, backpacks, duffels, etc., from discarded water and FanYogo sachets.

We went into the stadium around 2:15. The match wasn’t beginning until 5 but the gates were to be closed at 2:30 in order to “encourage” ticketholders to attend the opening ceremony in addition to the game itself. It worked. When President Kufuor and the heads of both continental (CAF) and global (FIFA) soccer governing bodies made opening remarks at 3 they were met with thunderous applause and not a little hornblowing.

The hour that followed featured a real spectacle with a cast of thousands: dancers, tumblers, men on horseback, etc. George explained that the first part was a visual retelling of

There was also the part where everyone came out with colored umbrellas and glided into perfect formations: the flag, the outline of

And that was before the game. A good hour before, actually. Once the spectacle ended the grounds crew came out and wadded up—did not roll up—the field-size white tarp and carried it off with some difficulty, revealing a yellow surface covering the middle half of the field. Many more workers rushed out from three directions with big cardboard boxes on their heads and ran to the edge of the yellow amoeba, which they began to dismantle pixel by pixel from the outside in. The amoeba was made up of thousands of interlocking tiles intended to protect the grass below. This was less of a precision drill than the performance. Tiles were removed in odd strips and shapes and thrown haphazardly into the boxes, which were quickly filled and carried off, leaving the amoeba only half-dissolved, pixels bleeding out onto the pitch. Workers looked around at each other confusedly for a minute and then resumed their work, now carrying the tiles to the edge of the field and heaving them over a waist-high barrier into a buffer zone between the closest seats and the field.

George watched the jumbled yellow piles grow and spread in the buffer zone and plainly saw the result of poor planning. He lowered his head into his hands, chagrinned: “They have failed. The tiles should have been attached to the white cloth. This is terrible. They have disgraced themselves.”

Later, with the field clear, the teams limbered up, the starting lineups announced, and the sun finally sinking, the match began. All the fans’ noisemakers, flags, face paint, and road flares had survived three hours in the sun and were fully functional. We happened to be in the unofficial Guinean cheering section (

Towards the end of the first half two men walked up the steps towards our section carrying two large jute bags each. They stopped right near our row, unzipped the bags, produced two handheld foghorns, and declared, “Ten Ghana cedis!” Well, it was really a success. It wasn’t five minutes before they had sold all their horns to fans within twenty seats of George and me. Groups of people were pooling money to buy them.

What made them so great was probably the amount of sound you got in return for pushing a button with your pointer finger. Meanwhile, you could use your breath for screaming. One foghorn was easily equivalent to three or four plastic elephant horns in terms of decibels; and it produced a unique pitch which resonated with the cranial bones, creating the sensation of a balloon being inflated in the hollow pressure-point space behind all the listeners’ ears.

Understandably, they needed to be tested out. All possible combinations of short blasts, long blasts, and very long blasts were examined. The results were summarized in a comprehensive report consisting of a single continuous blast that lasted minutes and exhausted the compressed air in the foghorn of a man a few rows behind us. George, whose ears are tender, was beside himself. “We would have been better to see the match on TV,” he said; but I could tell he was enjoying himself.

The second half was coming to a close.

Afterwards, as we walked home past the cemetery, groups of wet fans with paint running down their faces lifted stuck cars out of the roadside ditch. There was music and honking in the streets, car horns and foghorns and plastic elephant horns.